Vn124.1 Analogical Guidance 2/23/78

This evening at dinner, my family enjoyed a good time at the expense

of Scurry, our Scotch terrier. Earlier in the day, Miriam had played

tug with Scurry, the object of their contention a squeaking toy mouse

she had given the dog. Scurry wrested the toy from Miriam and sat chew-

ing it out of reach. Miriam then rolled Scurry’s small ball across the

floor, and Scurry, the mouse grasped firmly in her teeth, bounded off in

pursuit. She caught the ball and appeared trying to pick it up but

failed because the mouse was still in her teeth and she was definitely

not willing to loosen her grip. After relating this story to Robby,

Miriam rose from the table to demonstrate Scurry’s bind by duplicating

the situation. Scurry would not cooperate; she kept the mouse and

refused to chase the ball. Robby wandered off and Miriam, a little

dejected, draped herself over the back of the couch.

But there, her interest rekindled, for she saw on my toyshelf a

puzzle she has been working at unsuccessfully for a week or more. This

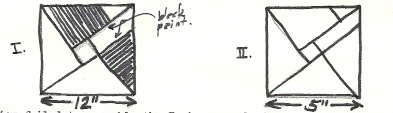

is the Pythagorean puzzle (cf. Vignette 77, Geometric Puzzles) which I

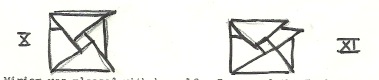

have realized in both 5 and 7 piece forms. This is their form, each

assembled as a single large square:

Miriam failed to assemble the 7-piece puzzle despite her repeated attempts

this past week. It is a vanguard problem for her. When she dumped out

the pieces on the couch, I asked her to bring it to the table and pushed

aside the dishes. Miriam complained, “I can’t do it.” When I asked why

not rhetorically and advised her it was just like the 5-piece puzzle,

she responded, “But I can’t do that either.” Miriam has done the 5-piece

puzzle. Her statement may mean she can not do it at will, without trial

and error, that she does not comprehend the puzzle. Miriam brought both

puzzles to the table but had trouble locating the center square which,

when found behind the couch, I kept.

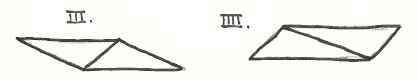

Miriam began with two congruent triangles, thus:

She declared the first a “yukky diamond” and tried, with no confidence,

to suggest the rectangle was a square. I gave her a hint: you have to

use all the pieces to make a square. Miriam then articulated a salient

bit of known knowledge: “This side has to be on the outside.” When

queried, she pointed to the hypotenuse of one of the congruent triangles.

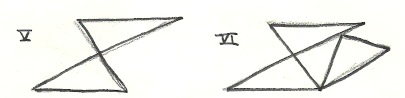

She tried, in order, these intermediate configurations:

As Miriam attempted lining up the corners of the 3rd triangle, she

pushed away the second from the first, saw the configuration below, and

held out her hand to me.

I gave her the center square, and she completed the puzzle. “Now do the

7-piece,” I challenged her.

Miriam laid the two complete triangles of the 7-piece puzzle on top

of the 5-piece assembly, arranged as in V, and noted, “I’m using the

same patterns.” She added the corner-cut-off congruent triangle; first

she put it in backwards, then as below. Her outstretched hand requested

the missing corner.

I gave her the missing corner and center square. Miriam tried the

smaller, similar triangle abutting the center square, then moved two

vertices to the periphery. She first tried the final piece backwards,

then completed the puzzle correctly.

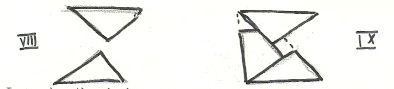

Miriam was pleased with herself. I removed the 7-piece puzzle and

asked, “Can you make a black-colored square?”

When she had done so, I asked if she could then make a gold one.

Miriam asked, “Do I have to use the square?” I said she should try to

without it.

Arrangement XIII showed Miriam she needed the little square which I

returned to her. The 7-piece puzzle followed. Miriam was stuck for a

while. One hint crystallized her completion of the 7-piece puzzle:

“Find a shape the same as this black part.”

Miriam located the end-cut triangle and fitted the smaller triangle

to it. She proceeded to build a column of these pieces, then added the

rectangle of 2 triangles in the appropriate orientation.

Voila!

Relevance

Several themes seem to arise clearly here. Some relate to the

precipitating situation: stumbling into problems accidentally when

the materials are at hand; the existence of this unsolved puzzle as

an item on an internal agenda to be worked at till mastered.

Miriam retained a very specific piece of knowledge as a key element

of the solution: “the long edge goes on the outside.” She was able to

use generally formulated advice when it had specific and obvious appli-

cation (e.g. use all the pieces) as well as very specific direction

(e.g. find a piece with the same shape as the black area). Trial and

error plays a large role.

Finally, for this difficult 7-piece puzzle, the combination of a

few hints and an analogous, simple version about which 1 key point was

known operated as guidance as effectively as do the pictures on the

surface of a picture puzzle.